k - and g - (as in gnawe and knight ) are voiced.However, unlike ModE, all letters are sounded, including those letters that are silent in ModE:

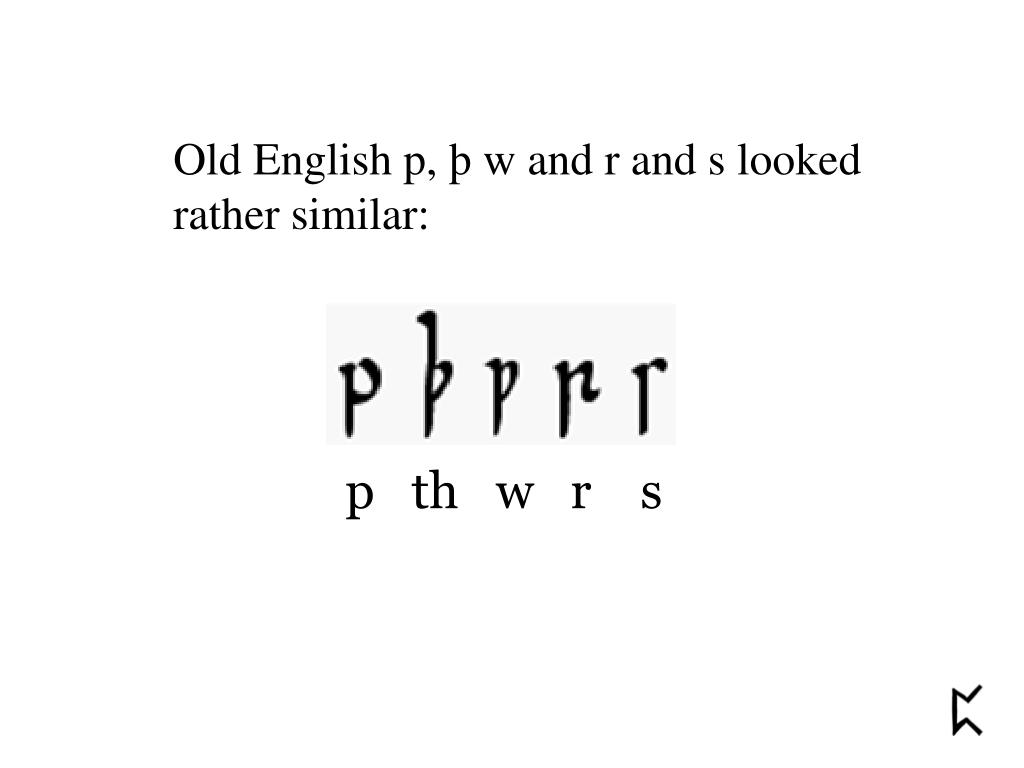

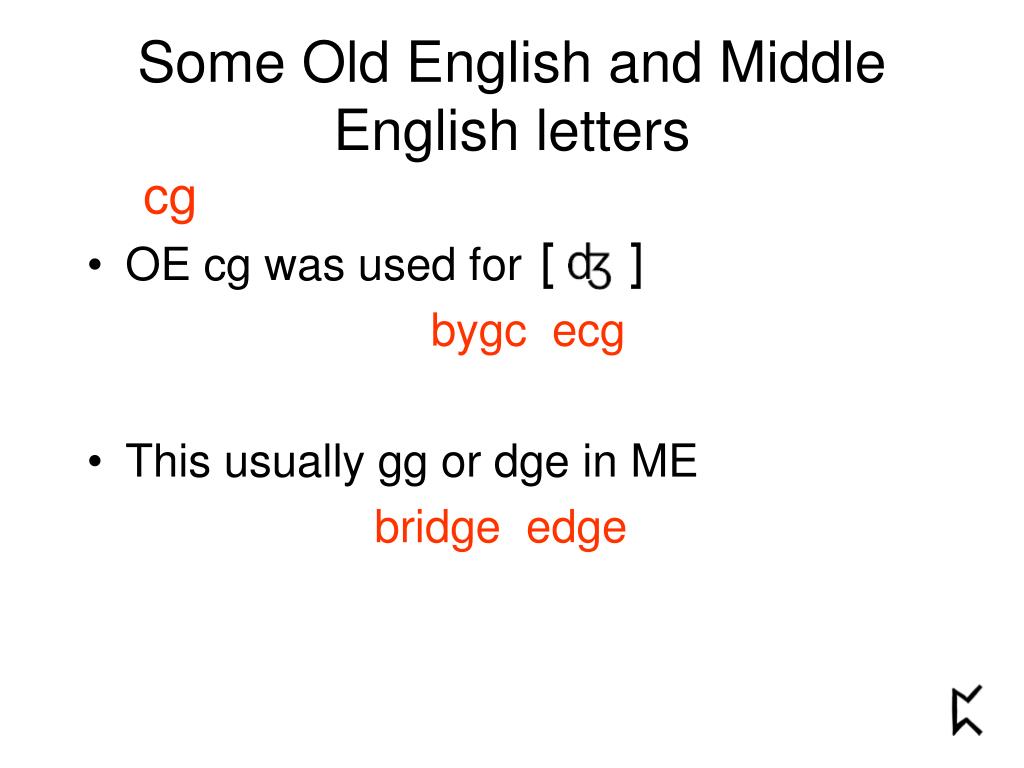

Most consonants are pronounced as in ModE. Don't fear them - they're fun characters to wow your parents with. You may, however, encounter them when using the MED or reading non-normalized texts. These have been normalized to their contemporary counterparts in the student editions we are using ("th" for þ and đ, "g" or "w" for yogh), so you won't need them on a daily basis. There are three Middle English characters that we no longer use: the thorn (þ) the eth (đ ) and the yogh (I don't have it on my computer, but it looks rather like a squared-off 3). Middle English is more inflected than ModE, so be aware of object pronouns ("him") preceding verbs - they are NOT grammatical subjects. Read logically when it comes to pronouns, and you'll be right most of the time. In others, “she” or “they” might look like “him,” so be wary from text to text. In some texts, he/she/they will be spelled recognizably. "Me thenkest" = "It seems to me," NOT "I think" Reading Middle English is an experience of interacting WITH the text, not being a passive consumer OF it, and your margins should be your personal road map to your interaction with the poetry. Similarly, if you have to look up a word or if you stumble over a syntactical construction, write down the definition or ModE word order in the margin.

Textual divisions are few and far between in most Middle English texts, so mark major structural changes in the margins. On the other hand, there are (for example) many words that mean "person" or "man," and you can often figure those out solely from context. Many words ("fre," "hende," "honeste") have a wider variety of connotations in Middle English than they do in ModE, so you will want to take regular recourse to a dictionary to ensure that you understand the range of possible meanings. Use the MED and/or OED, but also improve your contextual comprehension.

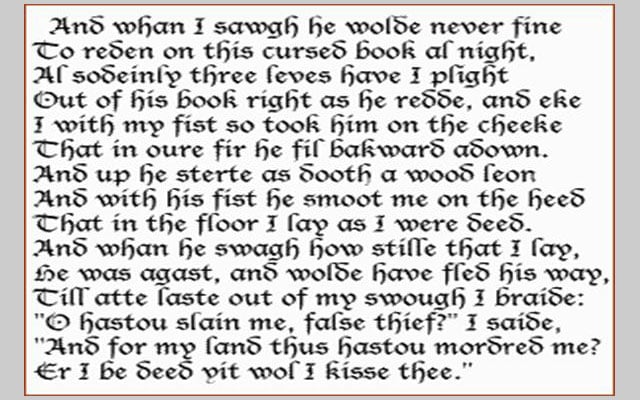

At the same time, there may be true grammatical, lexical, or cultural barriers to comprehending the text don't hesitate to ask me about these, because if you are confused by them, probably others are as well. If you see the phrase "He was the hendest man olive," you can be sure that the writer is not talking about kalamatas, but rather that he is using an o rather than an a. Few Middle English writers are trying to trip up their readers, so if you are presented with a seemingly illogical sentence construction or word, take the simplest grammatical or denotative path (at least for starters). Keep the accompanying pronunciation guide to hand, but also keep in mind that vowel sounds (in particular) may shift somewhat from one dialect to another. There are no silent ks or gs the final e is ALWAYS sounded as a schwa (unless it is a terminal y sound, as in "hende" = "handy"). (It's a good way to avoid odd looks from your roommate or cat.) You might want to form reading groups for this class, in which you gather to take turns reading the texts to each other. Moreover, because of the phonetic "spelling" conventions, words seen with the eye often make more sense when heard with the ear. Most Middle English literature was written to be read out to a crowd of listeners, and its poetry (and prose) is more comprehensible via ear as well as eye. And in courses where the texts come from a variety of locales and time periods, you will find substantial spelling changes from poem to poem reading phonetically (and being flexible about vowel pronunciation) will improve your comprehension and reading speed. There is no spelling consistency in Middle English authors and scribes wrote what they spoke (and heard).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)